The 10 Best Sushi Making Kits

This wiki has been updated 38 times since it was first published in February of 2016. Whether you're familiar with the intricacies of maki and nigiri or you're new to the world of Japanese cuisine but keen to become acquainted, you may be interested in one of these sushi making kits, so you can do it yourself at home. They'll let you create a variety of delicious rolls using your preferred ingredients, so you can impress your family and friends or just enjoy a healthy meal. When users buy our independently chosen editorial recommendations, we may earn commissions to help fund the Wiki.

Editor's Notes

December 01, 2020:

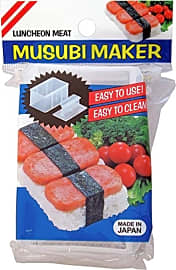

For this update, we removed the Easy Roller, which it turns out is not that easy, and the Camp Chef Sushezi Roller, as there are kits which include that roller along with a lot of other equipment for a similar price. The Aya 11-Piece is still fun for making novelty shapes like squares and hearts, and the JapanBargain Musubi Maker isn’t terribly versatile, but because it does its one job really well we still recommend it, especially for the Hawaiian snack Spam musubi.

We welcome Sushi Ninja to the list, as it’s got lots of fun bells and whistles including a nifty avocado slicer. Joining the Delamu Beginner is its sophisticated cousin, the Delamu 20-in-1, an all-in-one kit that has everything you need for various kinds of sushi except the rice, nori, and fillings.

Hardcore aficionados may want to invest in a sushi knife or in specific sushi serving plates. Find the best sushi-grade fish you can locate, pick the kit that’s right for you, and enjoy the fruits--or nori rolls--of your labor.

December 18, 2019:

Depending on whether you prefer simple and traditional or more elaborate and modern, you can find it in the Bamboo Worx Deluxe (for the former) or the Sushiquik Super Easy (for the latter). These have the pieces you need to get started, so all you have to do is provide the edible ingredients. The Aya 11-Piece remains a top choice, as well, especially since it arrives with a sushi knife and molds in various shapes, including a heart, so you can show your date just how you feel. We decided to keep the Camp Chef Sushezi Roller, a "sushi bazooka" that can be quite fun to use once you get the hang of it, and added the JapanBargain Musubi Maker, for crafting Spam musubi. And we opted to remove the Kitchen + Home DIY at this time. It isn't all that intuitive, and the instructions leave a lot to be desired.

One final word — it can be perfectly safe to prepare your own sushi at home, but pay attention to the quality of the fish and how it is handled, both before and after it gets to you. After all, foodborne illness is sure to put a damper on your culinary adventures.

Special Honors

Baycliff Company Sushi Making Kit The Baycliff Company Sushi Making Kit is a decent value for the cost, especially considering that it includes everything from wasabi to rice; however, most of these items are edible, which means you don't receive many reusable pieces. The cookbook is a nice touch for those who prefer real paper to digital downloads, though. sushichef.com

Williams Sonoma DIY Sushi Kit The Williams Sonoma DIY Sushi Kit has everything you need to try your hand as a sushi chef — except for the fish, of course. The booklet it comes with has plenty of guidance on how to get started, and it even outlines sushi etiquette and culture, so you'll be sure to avoid any embarrassing faux pas. williams-sonoma.com

Rolling With My Homies

The rolling kits are slotted bamboo mats that roll up on themselves into neat cylinders.

For some reason, the prospect of making one's own sushi intimidates a lot of otherwise very capable and confident chefs. I, too, was a little put off by the task when it was first suggested to me. Considering the fact that a simple vegetable roll will run you upwards of 5 bucks anywhere you get it, however, I figured I didn't have that much to lose.

The such making sets on our list seek specifically to remove all the mystery and difficulty from the sushi making process, though there are two distinct ways that they go about it. Essentially, you have traditional rolling kits, and you have what one might call sushi molds.

The rolling kits are slotted bamboo mats that roll up on themselves into neat cylinders. If you lay one out with nori (seaweed), rice, and any fillings you desire, you can roll the mat up with the sushi materials inside. When you unroll the mat, the sushi roll remains in a lovely log form.

The molds work by gently using pressure to force the rice and fillings into a piece of nori placed in the bottom of the mold. They are the easier device to use, by far, but they don't give you the same kind of cultural thrill that the traditional sets offer.

A few of these kits also come with recipe books and guides, as well as mixing bowls for your sushi rice and little slotted serving dishes that also work as cutting platforms to give you an evenly sliced roll.

Rice To The Finish

A lot goes into the preparation of sushi. Most people will tell you that the actual rolling technique is the hardest part, but if you spend an hour at the counter of a busy sushi restaurant, you ought to be able to watch the guys at work and pick up enough specifics to fair just fine on your own.

That balance is pretty specific to each chef, but, in my humble opinion, I've always leaned a little more heavily on the vinegar than the sugar.

What most people don't realize going into their first sushi assembly is that the rice is probably the most important aspect of your roll, after the quality of the fish, of course. Sushi rice is a very specific grain prepared in a very specific way, and all the fresh fish and rolling techniques in the world can't save you from bad sushi rice.

Good sushi rice isn't just cooked sushi rice; it also requires seasoning. Traditionally, you should season your sushi rice with a balance of rice wine vinegar and sugar, with a pinch or two of salt to make it pop. That balance is pretty specific to each chef, but, in my humble opinion, I've always leaned a little more heavily on the vinegar than the sugar. Not only does this create a slightly healthier role, I think the vinegar does a better job of highlighting the flavor of the fish.

As we mentioned above, the big divide among these sets is the difference between the more traditional rolling mats and the easier, less aesthetically appealing molds. With a good rice recipe, either set will make you absolutely delicious sushi. If you're impatient to get eating, I'd say go with the molds. If you really want to learn the art, I'd say get the mats. If you're a sushi fanatic who wants to learn the art, but also wants to eat sushi all day every day, I'd say grab one of each.

Out Of Isolation

While sushi is most closely associated with the island nation of Japan, its development reaches back a few hundred years before the dish hit Japanese shores. Originally, inhabitants of Southeast Asia wrapped fish in fermented rice as a way of preserving it. It's not unlike the western practice of salting beef, but it has the distinct advantage of being ridiculously delicious.

Originally, inhabitants of Southeast Asia wrapped fish in fermented rice as a way of preserving it.

The technique came to Japan in the 8th century. Later, during the Edo period, Japan's economy prospered immensely, and fermentation of fish for long periods of storage, especially in the cities, became less of a necessity. As a result, city-dwellers still ate fish conveniently wrapped in rice, but done so freshly and not by way of any fermentation.

During this time in Japanese history, however, the country was still fiercely isolationist, and it wasn't until the end of the Edo period and the beginning of the Meiji Restoration in 1868 that Japan opened her shores to more western commerce than just the occasional Dutch merchant.

It took a few decades, but the restoration period sent scores of Japanese immigrants to American shores, and they took their sushi-making prowess with them. At the same time, Japanese food, decor, and even some custom gained popularity among the American elites, and we can find an early reference to sushi served at a social function from 1904 in the Los Angeles Herald.

Soon, however, anti-Japanese sentiments cropped up among nativists, and they prospered enough to manifest heavy restrictions on Japanese immigration. Then, there's that chapter in American history that is only quietly talked about in high school history curricula for one or two days in each student's life, when, during the second world war, the US interned over 100,000 Japanese-Americans, the majority of them American citizens.

After that, there was an understandable lull in the production and popularity of sushi, which, thankfully, has given way to a second, seemingly unstoppable wave of enthusiasm over the dish.