The 10 Best Film Cameras

This wiki has been updated 40 times since it was first published in July of 2015. For all you old school snappers out there who still appreciate the quality of celluloid, one of these film cameras will give you the shots you're looking for. Whether you're returning to an old hobby or just learning to shoot, there's something here for everybody. There are even some throwback instant options on our list that are great for use at parties or by anyone feeling nostalgic. When users buy our independently chosen editorial selections, we may earn commissions to help fund the Wiki.

Editor's Notes

January 28, 2021:

For this update we replaced older instant cameras from Fujifilm and Polaroid with newer models such as the Fujifilm Instax Mini 11, Fujifilm Instax SQ1, and Polaroid Originals Now. These devices may seem pretty similar to their predecessors, but in fact they offer several distinct benefits, such as improved lenses, automatic exposure and focus controls, and superior builds. While the aforementioned options are focused on fun, convenience, and affordability, we also added the Leica M-A Typ 127 to fill out the high end of our list. It's an expensive choice, but it might be worth considering if you're a very dedicated photographer who prefers a fully-manual experience.

May 22, 2019:

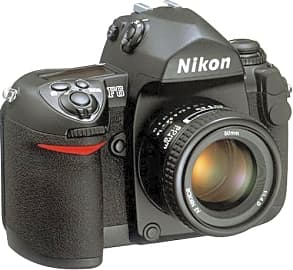

Given its ubiquity among film shooters for the past several decades, the Pentax K1000 easily retained the top spot. The fat price tag on the Nikon F6 cost it one position, slipping to number three after the newish Fuji Instax Mini 90. That Instax replaces the Wide 300 on our previous ranking, which was a fine camera, but that suffered from its 95mm equivalent focal length. A lot of people like to use these at parties, and that tight of an angle is tough to shoot indoors in close quarters without cutting somebody out of the frame. We also swapped out the Kodak Funsaver for the Fuji Quicksnap. The latter has a slightly larger flash button that should make for less fumbling about just before you take your photo, and since Fuji didn't have the temporary lapse in production that Kodak had in previous years, it's likely in better shape to produce a consistent product. It also comes in at an ASA of 400, as opposed to Kodak's 800, making it superior for outdoor daytime photography.

Everything Old Is For Hipsters

All the cameras on our list either operate with standard 35mm stock, or with proprietary instant development film akin to Polaroids.

At a certain point in our recent history, being on the cutting edge ceased to be cool. Conversely, there was a time when having your hands on the latest technology was the ultimate status symbol. There are still sectors where this ethos rings true, particularly in the cell phone market, but another subset of individuals seems intent on ruining everything nostalgic by co-opting its aesthetics and almost willfully ignoring any deeper underlying benefits.

I'm talking about hipsters, the great, benign blight on modern urban society. If it's a piece of technology developed after 1980, they don't want to know about it – unless, of course, it's something brand new that's designed to look like something produced before 1980. Theirs is a superficial movement, after all.

The shame of it is that hipster culture uses some of the coolest stuff mankind has ever produced, technological advances that are arguably better suited for their purposes than their modern equivalents. Vinyl records come to mind, the bit rates of which offer much deeper bass, crystalline highs, and a generally more dynamic sound profile than the digitized, over-compressed micro-files that stream through the airwaves to your Pandora station.

Film cameras have, for better or worse, fallen victim to trendiness, as well. The only bright side is that it's helped keep film itself in production by companies like Kodak, who have consistently threatened to close up shop. And without that film, these cameras become vintage paperweights.

It's that film that makes all the difference. All the cameras on our list either operate with standard 35mm stock, or with proprietary instant development film akin to Polaroids.

A few of these are SLRs, or Single Reflex Lens cameras, which use pentaprisms and mirrors to reflect incoming light through the lens and to your eyepiece. When you fire the shutter, the mirror moves out of the way and the shutter doors open to expose the film to light for however long you've set the camera to stay open.

Degrees Of Control

In addition to the SLRs described above, and the Polaroid-style cameras mentioned just before that, there are some cameras on the market that you actually build yourself. Such a camera is perfect for a curious enthusiast, a youngster interested in photography, or a serious student looking to bolster his or her knowledge about a film camera's inner workings.

If you're trying to learn photography as a skill and an art form, the SLRs on our list are your best bet.

Each of the cameras on our list has its appeal to a specific type of photographer, sometimes determined by the kind of pictures you want to take, and other times determined by how you want to be perceived as you take those pictures.

While the camera that you actually build yourself is great for students to learn about a camera's mechanics, assembly, and maintenance, it doesn't make the best camera for studying actual photography. There are too many risks involved in the build process that could confuse a young student about exposure levels and the results they can expect from a certain combination of settings.

If you're trying to learn photography as a skill and an art form, the SLRs on our list are your best bet. These, when used in their manual modes, will put you in control of your shutter speed, your aperture, and your focus, so that you can take total control over the exposure, composition, and clarity of your images.

While the instant cameras on this list are more for fun than anything else, they, too, present the possibility to create great art. The problem with these is that they have very few variables for you to adjust, you're stuck at one focal length, and you have no control over the developing process beyond shaking the photo to make it develop faster (side note: that actually doesn't work).

Film's Slow Development

While nobody technically exposed a single photographic image until 1816, when one man temporarily exposed portions of a sheet of paper coated in silver chloride, there has been a kind of image capture available to us reaching back many millennia.

The first of those immortal experiments were the Daguerreotypes and calotypes of 1839 and 1840 respectively.

The camera obscura significantly predates modern photographic equipment, but its design led inventors experimenting with potential techniques for immortalizing images to the film exposure and development processes still used today. The first of those immortal experiments were the Daguerreotypes and calotypes of 1839 and 1840 respectively.

George Eastman, founder of Kodak, sold his first paper film stock in 1885 before eventually switching to celluloid film about four years later. He also produced the first cameras intended for mass consumption, two simple, box cameras that were inexpensive enough for a great many people to afford.

The first 30 years of the 1900s saw the gradual but significant rise of 35mm as a film standard, with the Japanese company Canon releasing its first 35mm rangefinder in 1936, just as the country's war with China began to reach epic, and eventually global, proportions.

From there, camera manufacturers like Nikon and Pentax poured resources into SLR technology that shot 35mm over all other formats, and even after the digital revolution came and threatened to wipe out film as we know it, those 35mm SLR designs persist as the standard bearers of film photography.