The 10 Best Electric Fence Chargers

This wiki has been updated 32 times since it was first published in October of 2017. Whether you're a rancher who needs to keep livestock secure or a gardener who just wants to prevent animals from feasting on your precious vegetables and flowers, an electric fence charger can offer the protection and peace of mind you desire. When shopping around, it's important to avoid models with continuous current, as it's possible for pets to get stuck on them and be electrocuted. When users buy our independently chosen editorial picks, we may earn commissions to help fund the Wiki.

Editor's Notes

November 14, 2020:

When setting up an electric fence, energy source and land area go hand in hand. If you're trying to protect a garden or small plot of land, the assumption is that this plot of land is near your house, meaning a unit that runs on AC power should be fine for you. You also may not need this charger to be weatherproof, since it can sit in your garage or shed. The best AC units still have quite a bit of range and power, such as the Parker McCrory Digital, M300 by Gallagher, Patriot PMX350, and Red Snap'r AC. As you can see, the bulk of the top 5 this time around is made up of units like these, as they are durable and powerful, and meet most people's needs.

There are those who have other considerations, however, which is where battery-powered models come in. If your plot of land is far from your house, or at least far from electricity, AC power won't do you much good. The best battery-powered models don't just have batteries, but solar panels, which allow users not only to ensure their fences are operational at any time of day, even when the power goes out, but also can save on electricity costs. The Parmak Magnum is a great option, but the clear winner this time around is the Gallagher Solar because it's uncomplicated, water resistant, and easily portable.

May 15, 2019:

Safety is most likely your number one concern when it comes to electric fence chargers, followed by efficiency, and we still think the the M300 by Gallagher and the Parmak Magnum tick both of these boxes. For the distance they can cover, they're both fairly priced, although the Parmak is more expensive — typical of solar units. Also, the the Parmak is designed specifically for weatherproof use, whereas the M300 should be protected from rain and other sources of moisture. Again, however, this is typical of the difference between solar and non-solar options. If your needs aren't quite as robust, the Fi-Shock Low Impedance remains an option to look at. It has low internal resistance, which helps it keep the fence powered even in areas where there are a lot of weeds. You might use it to keep your garden safe. Finally, we decided to add a perhaps unconventional choice, the Udap Bear Shock. It is made to ensure camper safety by providing a perimeter around areas for food or sleep; of course, this might be overkill on casual camping trips, but for explorers heading off into the deep woods, it may provide necessary peace of mind.

Special Honors

Gallagher M10000i The units on our list are fine for smaller plots of land, but if you're dealing with a massive land area, you might be willing to overlook the high price of the Gallagher M10000i. 100 joules, 1,000 miles, 6,000 acres - this is some serious capacity. gallagherelectricfencing.com

A Brief History of Electric Fences

This can allow your livestock to escape, or worse, your T-Rex to go on a murderous rampage.

Electric fences have been around for a lot longer than you might think. In 1886, a man named David H. Wilson built a 30-mile fence that was powered by a water wheel. It wasn't terribly effective, but the idea was out in the world.

The next time electric fencing would be used would be for more nefarious purposes. During the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, the Russians set up fences that were charged with up to 3,000 volts. The fence had the opposite of its intended effect, however, as the Russians were far more frightened of it than were the Japanese, who easily circumvented it with insulated wire cutters.

The Germans also used them during WWI, and they built a 300 km "Wire of Death" across the Dutch-Belgian border. The fence truly earned its nickname, too, as it killed several thousand people.

Things calmed down considerably in the 1930s, however, as fences returned to being primarily used for agricultural purposes. They began to spring up across the United States and New Zealand, and it was the New Zealanders who would introduce pulsed fences. A man named Bill Gallagher needed to devise a way to keep his horse off his car, which was apparently a big problem in New Zealand in the 1930s.

He used the ignition coil on his vehicle to charge his fencing, and while it was effective at keeping his horse at bay, it had other issues. It used a current that was prone to emitting long, unpredictable blasts of electricity. There was also the slight issue of causing fires, which seems bad, but then again we're not ranchers.

One of Gallagher's countrymen, Doug Phillips, used a capacitor to make a non-shortable electric fence, which made it possible to greatly extend their reach while also significantly reducing costs. A farmer from Iowa, Robert Cox, took care of that whole brush fire problem in 1969 by improving the fence brackets, which enabled the wires to be lifted higher off the ground and away from flammable grass.

Since then, various improvements to materials, such as the use of polyethylene insulators and high-tensile steel wire, have allowed these fences to be much more practical and cost-effective. They're actually often less expensive and easier to install than regular fences, as they need less reinforcement, since they don't have to physically hold large animals back.

The biggest downside, of course, is that they can go down at an inopportune time. This can allow your livestock to escape, or worse, your T-Rex to go on a murderous rampage.

Choosing the Right Electric Fence Charger

Without a quality charger, an electric fence is just a fence — and a flimsy one at that. However, there might be more options on the market than you're expecting, and buying the wrong one can be an expensive mistake.

The first thing to consider is what, exactly, you need your fence to do. A charger that can power miles of fence and contain massive livestock will be different from one designed to protect your garden against smaller pests.

The answer to that question will go a long way towards helping you decide what kind of power source to use.

A charger that can power miles of fence and contain massive livestock will be different from one designed to protect your garden against smaller pests.

Many can be plugged in to a basic 110V or 220V socket, and these will provide continuous power at a low cost.

You can also find battery-powered models, which are excellent for remote areas, but these are more expensive and you'll really need to stay on top of changing those batteries.

The last category contains the solar-powered options. Obviously, you have to place these in an area that receives lots of direct sunlight, and they may not be ideal for areas that suffer through gloomy, overcast winters. You may be able to find hybrid chargers that use both batteries and solar panels, however.

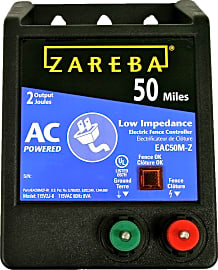

Ideally, you'll want to find a low-impedance model, as these are both safe and effective. High-impedance models can start fires, or even kill animals that get stuck on them.

The final thing to think about is how powerful you want your energizer to be — but that question is so important it deserves its own section, so keep reading.

Joules, Volts, and Amps: What Does It All Mean?

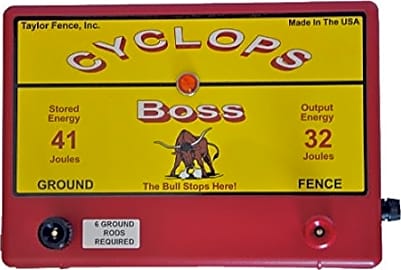

When comparing chargers, you might see two types of joules listed: stored and output. Basically, the stored number tells you how much juice is kept in the energizer, and the output is how much reaches whatever's being shocked. The output will typically only be about 60% of the stored number, because you'll lose some power as the electricity flows down the line.

As a result, the more fence you have, the more joules you need. The standard is that you should expect to need at least one joule per mile of fence.

Basically, the stored number tells you how much juice is kept in the energizer, and the output is how much reaches whatever's being shocked.

The voltage is the amount of energy running through the wires. Larger animals with thicker skin need higher voltages to deter them, and some escape artists — like goats — need plenty of discouragement to keep them from testing your fence for weaknesses. However, you don't want to fry smaller animals like chickens or your dog, so don't overdo it.

Be careful when looking at voltage, though. If you're using a plugged-in charger, there might be a voltage number that corresponds to the socket you can plug it into, not the amount of electricity that shoots out.

You might also see amps mentioned. This is the amount of electricity that actually zaps the animals. Think of voltage as the amount of water pressure in a hose, while amps are the amount of water actually coming out the end.

Keep in mind that electric fences are psychological barriers. That means that the shock should be just enough that the animal feels a sudden and alarming discomfort — you do not want to hurt them. Eventually, they'll associate the fence with discomfort and avoid it.

Also, if you choose one with dangerously high voltage, you'll feel guilty about tricking your buddies into touching it (don't do this).