The 10 Best Chinese Chefs Knives

This wiki has been updated 35 times since it was first published in October of 2016. Also known as caidaos, Chinese chefs' knives are very different from the butcher's cleavers they resemble, and serve nearly as many functions as Western designs. Known for their incredibly sharp edges, they're highly versatile, ideal for prepping large amounts of vegetables, crushing garlic and similar foods, and carving the thinnest slices of meat and fish, whether raw or cooked. When users buy our independently chosen editorial picks, we may earn commissions to help fund the Wiki.

Editor's Notes

September 02, 2020:

The first, and arguably the most important, thing to understand about Chinese knives if you want to keep them in good condition is that, despite how much they may resemble a Western cleaver, you should never cut through bones or similarly hard items with them. Instead, they should be used for the same purposes as a chef's knife, such as chopping vegetables, smashing garlic or ginger, and slicing boneless meat. Though often underutilized in most American kitchens, they are actually very versatile and will quickly become your go-to choice for a range of culinary prep needs.

While all will be lighter in weight than your average cleaver, the Global G-49/B takes that to the extreme, coming in at less than five ounces. This makes it a good choice for those who spend a lot of time prepping veggies, since it won't be very fatiguing. The caveat is that some may find the handle gets uncomfortable after extended periods of use, so if you are worried you might be in this group, you may be better off with something slightly heavier, but with a more ergonomic handle, such as the Shibazi Zuo S2308.

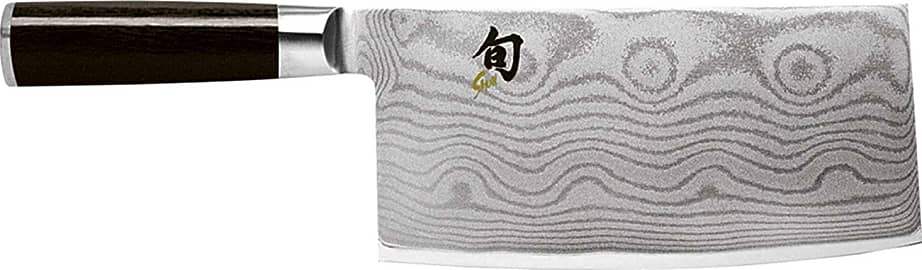

If you want something that is as eye catching as it is functional, the Shun DM0712 and Kyoku Daimyo Series Vegetable Cleaver immediately stand out. Both feature a large bolster that helps to balance out the weight of the blade, while also strengthening its overall construction and offering some finger protection. They also boast striking Damascus patterns, and the latter takes some inspiration from Western knife designs and features a triple-riveted handle, with the center rivet being a beautiful mosaic pin.

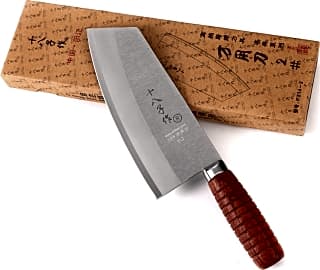

The Shibazi Zuo F208 and JapanBargain 1564 are both workhorses that would be well suited to a commercial kitchen where you don't want to waste money on fancy aesthetic features that aren't needed and simply prefer something that performs well. That being said, if you are willing spend just a little bit more, you may find the Zhen A5T offers a more comfortable handle, and, being made from VG-10 steel, can hold an edge longer.

March 23, 2019:

First of all, do not, under any circumstances, ever try to chop through as bone or other hard item with one of these. They may look a little bit like meat cleavers, but they are decidedly different. They're thinner, lighter, and made with harder steel, which prone (if not guaranteed in some cases) to chip when it's pounded through bones and joints. Aside from that, the caidao is a do-it-all workhorse knife, and it's important to get one that's comfortable and well-balanced, because if you do, you're liable to use it nearly all day long, finishing all sorts of different tasks. With that out of the way, you'll notice a handful of blades from Shibazi Zuo on the list. Believe it or not, these inexpensive models are actually used by legitimate pros around the world, and to get a higher-quality and more authentic caidao, you'll basically have to travel to China yourself. They may not look like super-fancy pieces, but they absolutely are some of the best. Shibazi's F214 is alittle bit different than most cleavers, as it actually has a tip, which is generally unheard of on a caidao. If you want to show off your taste a little, or these for any reason don't perfectly suit you, the Shun or Wustof almost certainly will, though they both come at steep prices. The JapanBargain is an interesting choce because of its rock-bottom price, though it will likely require a bit more attention than the rest to maintain in perfect working order. If your knife bag or case is already full of useful items and you are (like me) a knife nut, check out the Tojiro. It's awfully heavy and might not be suited to full-time use, but it's among the finest-crafted, and its fit and finish are both simple and supreme. And if you're just not a fan of the wa-style round handles common on traditional asian knives, try the Zhen or the Zwilling, which feature the more Westerm-familiar ergonomics, and are both reasonably good values at moderate prices.

Special Honors

Masakage Zero Nakiri With its striking dimpled blade and eye-catching mosaic pin in the handle that features a chrysanthemum design, you'll be happy to show off the Masakage Zero Nakiri in your kitchen. Its handle is made of ironwood, which is incredibly hard, and the blade's core is Aogami super steel, which is easy to resharpen. knifewear.com

Fujimoto Nashiji Nakiri 165 mm Hand forged by blacksmiths in Sanjo City, Japan and boasting a beautiful burnt chestnut handle is definitely a worthy addition to any knife collection. It is constructed with a Aogomi blue #2 steel core sandwiched between layers of stainless steel, which provides it with both edge retention and chip resistance. thecooksedge.com

The Knife: A Universal Tool

Blades were made of increasingly stronger alloys as technology allowed, including components like copper, bronze, and iron.

Millions of years ago, well before the emergence of modern Homo sapiens, members of the now-extinct Australopithecus genus were some of the first organisms to craft sharp tools from chips and flakes of rocks and bones. And while you might think that making blades out of rocks is an antiquated practice, keep in mind that modern surgeons still often cut with obsidian blades, as they can hold a noticeably sharper edge than carbon steel, helping wounds heal faster.

Blades were made of increasingly stronger alloys as technology allowed, including components like copper, bronze, and iron. Beginning in the Iron Age over four millennia ago, craftsmen began to develop highly effective ways to work metal, resulting in more durably forged equipment that lasted considerably longer. The introduction of additional metals eventually led to stainless steel, which doesn't shatter or rust anywhere near as easily as iron.

Powerful materials and efficient machining techniques contributed to knives becoming common household items, though it would take quite a while for short swords and daggers to evolve into something resembling today's kitchen knives. The European middle ages saw an incredible increase in the popularity of single-bladed knives, much like the butter knife. This is partially due to a decree from Louis XIV after one of his ministers noted the correlation between deadly attacks and pointed, double-sided blades. Halfway around the world, though, an entirely different style was already an important part of the culture, drawing much influence from ancient swordsmithing techniques.

While many people are familiar with Japan's rich traditions of blade production, it's actually most likely that their forging methods originated across the Yellow Sea, in China. For this reason, blade composition and construction are quite similar between Japanese and Chinese specimens, though not identical. There's a much wider range of Japanese options, and while Chinese chef's knives aren't quite as varied, they're arguably even more versatile.

What's So Special About Chinese Knives?

Modern knives generally fall into one of two categories. These two classes are often referred to as Western and Japanese knives, which is wildly misleading. A slightly more accurate system might separate knives into heavy vs light, or soft vs. hard blades. While the name is debatable, there are concrete differences between the two camps.

Asian blades are crafted from a significantly different blend of metals with considerably different characteristics.

Heavier knives, originally modeled after German designs, generally have a somewhat curved profile, as well as a wider angle on the edge, and a thicker blade construction overall. One of the most important features about the so-called European style blades is that they're generally made of softer alloys than their Asian counterparts. Somewhat counter-intuitively, this actually makes German knives considerably more durable and versatile, because a tiny bit of flex goes a long way in preventing chips and cracks. A minor drawback of the more pliable metal is that the edges warp or curl, drastically reducing cutting ability. To combat this, heavy use of a German-made knife requires a honing steel within arm's reach, to keep your edge razor-sharp.

Asian blades are crafted from a significantly different blend of metals with considerably different characteristics. The chef's knives are exceptionally light and thin, with an especially slight honing angle of as little as twelve degrees on some high-end selections. Their stiffer and less tensile properties enable remarkably sharp edges — e.g., some chefs don't stop stropping until their eight-inch knife can shave hair. On the other hand, such sharpness calls for a lot more caution during use; you can't just hack away with an Asian knife the way you would with an old-school Solingen or a classic Sabatier. In fact, the steel, hardness, and potential sharpness of Chinese and Japanese knives are renowned around the world, and lend themselves well to maintenance using super-high-grit sharpening stones.

Whether sharpening or cutting, softer implements tend to be a bit more forgiving, and their increased heft offers more control to those who might not have years of kitchen experience. In general, Asian knives tend to be sharper, though only if they're properly maintained, and their slimmer profile helps them slide through food that a larger knife would smash or rip apart. It's important, however, to always work your knives by hand — never use a mechanical sharpener on a high-end knife. Doing so can cause excessive microserrations that may reduce a blade's effectiveness and overall lifespan.

Get Out The Chopper

Walk into a French, Japanese, or American kitchen, and you'll see dozens of blades of various shapes and sizes lining the walls. In Chinese homes and restaurants, however, it's far more likely that you'll see one tool doing the vast majority of the work. It is true that a lot of modern chefs prefer to stick to their primary knife, but the Chinese variety, known as the caidao, is specially constructed to add incredible multi-functionality.

Their characteristic rectangular profile is another very important feature.

First of all, they look quite similar to Western cleavers in many ways. The two are almost nothing alike, though, and share almost no kitchen tasks whatsoever. For example, you should never use a high-hardness, Chinese blade for breaking apart bones. For everything that's softer than a winter squash, though, these choppers are perfectly suited.

Their characteristic rectangular profile is another very important feature. A relatively straight edge, plus an extra-wide and squared-off profile, make this type of knife excellent for nearly any size chop or dice — their very name, caidao, actually translates into English as "chopper". The extensive surface area turns the tool into somewhat of a handheld prep surface, as well, allowing skilled culinarians to process, separate, and combine various ingredients with just a couple flicks of the wrist. And because their alloys are so durable, they can take and hold the kind of offset edge that you need for ultra-precise cuts like the fine brunoise, one of the truest tests of a prep cook's skill.

Ultimately, a knife is only as good as the metal in its blade, and the chef who's using it. As long as you exercise caution around all sharp tools, get in lots of practice, and keep your knives in prime condition, they should realistically last for many years.